Statement No. 014:

Dolan Dooley

Roughly three-quarters of the way to Joliet sits the unincorporated community of Doome. That's if you take notice. I've seen sneezing fits lasting longer than the time it takes to drive from one end of town to the other.

The place boils down to a flyspeck of a company town. They've got one business in Doome, and one business only: The Lakes Sanitarium. You're right if you're thinking it's got nothing to do with any great body of water. The closest lake is 50 miles away. A brother and sister act by the name of Lake established the joint in the last century. It beats me why all the way out in Doome. It sure wasn't on account of the waters. Of course you couldn't help but get a rest cure at Lakes; there's nothing else going. That's all quite a ways back, anyhow.

Since the 1920's it's been run as an asylum for the criminally insane. Or maybe the insanely criminal. Call it one of those half-full, half-empty propositions. Sure. It depends on which side your bread is buttered. It depends on contacts and funding and who you know in the state penal system. You boys get me.

Despite the massive structure, you'd miss Lakes from the road. It sits like a bunker, big as several city blocks. The unmarked turn-off snakes through a thick grove of birch trees surrounding the fortress. They could probably cram thousands of patients inside those stone walls. For all I know they do. But my yarn's only concerned with one inmate, Donal Dooley.

I owed Dooley, and Doome, a fourth and probably final visit. It hadn't snowed for better than a week, so the roads ran nice and clear. Getting into the joint went smooth. Lakes operates with plenty of barriers between you and its patients. I guess they could do what they liked, being a privately held outfit and all. They probably received few repeat visitors. But the routine eased with every pilgrimage. I guess they got used to me. They granted me the go-ahead and a uniformed guard escorted me to the Visitor's Assembly.

A fenced-in catwalk ran beneath the ceiling of the expansive hall. Row upon row of folding tables with built-in benches stood perfectly in line. They laid out the hall like any industrial lunchroom, no different from the dining facility in a big house. The joint achieved all the warmth of a state execution.

I chose a table halfway across the floor from the only other man in the room. The baggy, striped garments ID'd him as an inmate. He took no notice of me. He occupied himself with a constant stream of murmuring, like so much scatting. I couldn't make out a thing. The babbling echoes buzzed like an undercurrent across the cavernous space. He didn't break for a second when the heavy clang of iron doors carried throughout the hall. The entrance of Donal Dooley made no never mind to him.

Dooley hitched his way towards me with a shuffle and hop that accommodated his manacled ankles. Cuffs bound his wrists, too. A grim looking guard trailed Dooley by 10 paces. I describe him as a guard because the garb looked like straight, prison issue.

A wide, rubbery grin dominated Dooley's face as he approached my table—that's the face he always wore. He dropped on the bench and leaned back, swinging his legs up, over and around to face me. The seating routine happened in one smooth motion, natural like. As natural as drawing your hand to a yawning mouth, or tugging your pants when crossing your legs. It was automatic, second nature. Dooley could've done it in his sleep. This marked his ninth year as a Lakes resident. During a previous interview he explained that the Lakes hospitality accounted for the sloppy smile perpetually slapped across his mush.

Of course none of the trustees ever referred to Lakes by name. They employed all the prison parlay, but also invented plenty of pet names. Mostly you heard the dump referred to as Frendly House, Doome House and House of Doome. The simplest term sounded the sweetest, if you didn't know any better. "How long you been home?" "When are you leaving home?" "There's no place like home." You catch my drift. They didn't call each other patients, either. They were prisoners, cons, friends of Frend, Doome bugs, and just plain bugs.

Dooley turned his head side to side and eyed me while holding that dopey grin on his kisser. "Such a surprise to see you. I wasn't expecting no one."

"But you've probably got an idea why I'm here. Maybe you can you guess what brought me out to this godforsaken wasteland. It sure ain't for fun."

"Yeah, I guess I can pretty much guess, all right." He buried his tongue in his cheek and nodded his head. "I'm guessing you found something."

I found something, all right, thanks to Mr. Dooley. It took three, tempered interviews to reach that point. Three dead runs spread over a couple weeks before Dooley played his hand.

About two weeks earlier Dolan Dooley's mouthpiece engaged me on his client's behalf. Albert Snoot's figure imposed on you. He conjured up an image of the Michelin character squeezed into a pin stripe, his hair slathered with Brilliantine, a glistening handlebar mustache perfectly balanced over his petite mouth.

At first Snoot described the job in vague terms. He said he represented a client who wanted to meet with me. Just to chat, as Snoot put it. Depending on the first interview, more details would be forthcoming. Sounded more to me like a radio game show than a job.

Imagine my surprise when he wised me up to the particulars. His client had been brought up on armed robbery and manslaughter charges. Our two-fisted D.A. won his case, all right, but the court found the defendant to be a certified nutcase and transferred him to Lakes. I'd have to drive out to nowheresville for my audience with the great Donal Dooley.

That's all Snoot would give out. He claimed ignorance as far as Dooley's intentions. But he did put on the gallant act and all, claiming that Mr. Dooley recognized and acknowledged the peculiar circumstances inherent in this request—those are mostly Snoot's words. Naturally the clock would start running the moment I headed out for Doome, if I found that copacetic. Fair enough, I thought. If Dooley via Snoot wanted to pay me for a day's work just to drop in on a bughouse, that was okay with me. Besides, I got kind of curious. What could a convicted felon have in mind? Or what could he think he had in mind? A lot of it would boil down to exactly how many bats flew around the belfry.

I asked Snoot exactly how far gone Dooley was. I told him not to get me wrong, that I wanted the fee, all right. I just didn't go for getting paid for nothing, I told him.

Snoot raised his bulk out of the straight back and made for the door. He cracked it open, then swung to face me. He assured me of the legitimacy of Mr. Dooley's proposition, one hundred percent. He gave me his word I would be neither wasting his client's time nor money, and that Mr. Dooley eagerly awaited my company. As far as judging the workings of a mind, what could a humble attorney possibly offer? Snoot's handlebar curled up and his chubby palms reached out before him.

I let Snoot hold that imploring pose while I lit a cigarette. I could only shrug and tell him that I'd take a flyer. I'd be out in two days, I told him. Sure.

Snoot's thick head nodded on his thick neck and he almost departed. Before the door shut, that big head stuck back through the opening. Snoot wanted to add, off the record, that Dooley was no crazier than he was. That comment made everything as clear as using a New York City transit map in Budapest.

The record showed Dooley had been a busy boy. His rap sheet read long enough to put the average hood to shame. By the time I came on the scene, Dooley had spent 19 of his 45 years behind bars, in one form or another. He got his first taste of juvenile hall when he was 11, in and out five times before the age of 18. He was arrested as an adult for the first time at 19, but he beat that rap. He made his first trip to the big house when he was 20.

Dooley liked precious things and he liked flourishing a gat, so mostly he undertook daywork. He fed on a steady diet of jewelry store heists, usually pulled alone. That sounded a little crazy at that.

Dooley tried a high-profile job his last time out. The stick up of a North Michigan Avenue jeweler went south plenty fast. When the cops responded to the alarm they found two gunshot victims, the store guard and a customer. The customer died that night. They discovered the great Dolan Dooley two blocks north, doubled up by a curb, nursing a lower leg shattered by a slug. Through his arrest and convalescence, Dooley claimed his innocence. He didn't remember a thing, he said. Snoot presented Dooley as the victim of a horrific blackout and the court couldn't prove otherwise, at least not beyond a shadow of a doubt. Twelve good men found Dolan Dooley guilty with extenuating circumstances.

The arrest record noted that Dooley and his wife had separated. He had one daughter. No other family. And that about wrapped things up for Dolan Dooley. A 45-year-old man who'd pulled his last job. A man set up for life the hard way. He'd never see nothing from the outside again.

I kept that little file of info in my head during my first visit to Lakes Sanitarium. I didn't get a whole lot more out of Dooley. He confirmed enough of his record to verify its accuracy, for the most part. And I learned he smoked Chesterfields. Other than that he told me zip. He refused to say a word about his wife or his kid. He offered no details about his last arrest or his time at Lakes. He said boo as far as why he wanted me there.

Dooley never stopped smiling. Real casual like, he was. To the guards and other visitors we must've looked like a couple of old pals just shooting the breeze. But Dooley felt me out plenty, in his own way. We talked some about my background and cases. He got all curious when I spoke about dealing with the cops. He asked what it's like, working with the bulls. I told him it always felt like taking a dose of the worst tasting medicine. And that the bad taste can last for a long time. All in all, I said, coppers usually got a raw deal.

I thought Dooley might squawk at that, but the silly grin never left his pan. He just kept sizing me up. He asked about my drive down to Doome, how was business, if I'd ever been arrested. The conversation played like that for about 45 minutes.

Dooley dodged every straightforward question I threw at him. As far as I could tell he just wanted to get acquainted. When he swung himself off the bench to stand, he said I should come back in a couple of days. I asked him if that was it. He said, yeah, that was it. I pointed out that the clock kept running. He threw me that full, crazy smile and repeated that I should come back in a couple of days.

Donal Dooley struck me as plenty lucid. As far as I could tell, to use courtroom jargon, he appeared in complete control of his faculties. I have to say I became intrigued trying to figure his game. I spent the ride home puzzling it out. Not that I got anywhere. Not that I expected to get anywhere. Dooley gave out nothing to go on but the slightest circumstances I've already described. Try decoding a message from a partial cipher—you end up working mostly from inference and context.

Dooley had something on his mind, something he couldn't do from the inside. But he didn't turn to Snoot. Either the deal wasn't up Snoot's alley or Dooley mistrusted Snoot. Maybe Dooley couldn't trust anyone else he knew, or he just plain mistrusted everyone. I figured he mistrusted the world. So he's stuck in the Doome House with no one to turn to but little, old me. Ain't that rich? Sure.

That's why Dooley had to get to know me. He had to feel me out. He had to learn how far could he trust me. And how far along could he string me. Dooley must have been plenty stuck. After nine years in the loony bin, something forced his hand. Pressure came from somewhere. Enough to make him turn to a stranger. Sometimes you can trust strangers more than your closest friends. Sometimes a stranger can be the great equalizer. There's no disadvantage with a stranger, least wise not starting out. Strangers level the playing field.

So you could say Dooley captured my interest. I'd play along for at least one more round. I'd give him one more shuffle and see how he dealt the hand. That's what I reported when Snoot telephoned. He sounded real pleased with the whole affair and emphasized the fact. I pointed out that it didn't matter whether he was pleased or not. Dooley was my client, not him. I couldn't care less what he thought. That got him stammering for just a moment, but he finally got it out that he agreed. He took it on the chin, just like a good, little boy with a fat, little retainer should. Sure.

I stuck to my guns and tooled down to the wastelands of Doome two days later. It took under an hour to maneuver through the red tape rigmarole. That cut the processing time down by more than half compared to my first go-round. I found three other tables occupied in the Visitor Assembly. One of the tables hosted a rather heated exchange between a young inmate and an older man. I spied a heavily made up broad making like Niagara Falls before a stupefied Doome bug. The poor gink kept throwing up his hands and shaking his head. The last inmate sat by his lonesome, talking up a storm to himself. The hall's acoustics made it impossible to understand anything anyone else said. The voices blended together like a muted, subterranean rumble with an occasional crescendo provided by the blathering broad. That was just dandy with me.

Dooley shuffle-hopped his way into the hall with a guard in tow. He spotted me at once and made his way over, his pan lit up by that perpetual, goofy grin. He swung himself onto the bench across from me and laced his fingers in front of him. His eternal, sloppy smile had its effect, all right—you couldn't tell what the hell he had on his mind. You couldn't perceive how anything registered with him. You couldn't fathom what he noticed or didn't notice. Your guess would've been as good as mine.

He began our conversation by telling me he was glad I could make it. I told him I was thrilled that he was thrilled. I dug a pack of Chesterfields out of my jacket and flipped the deck across the table. He picked up the pack, tilted it in his hand. He looked me in the eye, tapped the pack two times on the table, and broke it open. He popped a stick between clenched teeth and turned toward the guard. Dooley gave a slight, backward jerk of the head. The guard nodded slowly.

Dooley told me they didn't allow the inmates to play with fire. I struck a match and he leaned the cigarette into the flame, keeping his hands under the table. He drew a long, deep drag with his head tipped back. Then he began to talk.

Dooley opened up enough to describe his stay at Lakes. He spoke of his nine years spent keeping up a front. He wasn't nuts. Sure. Half the Doome bugs weren't hardly crazy at all, he shrugged. Nothing dangerous, anyway. Some of the bugs, he said, you had to watch out for. And the staff, too. Accidents were known to happen at Lakes. You see, no one ever suffered any kind of willful attack. Inmates never targeted each other. Neither did guards or orderlies. As far as the state knew, Lakes had a clean bill of health. Tranquility reigned at Lakes. But there were accidents.

Just last week two fish fell down a whole flight of stairs. Snapped their necks. Both of them. Recently an orderly lost his footing and sort of fell off a catwalk. And then, every once in a while, a guard or a bug would have the misfortune of slipping in a gangway, or on their cell floor, or in the shower, maybe, and cracking their skull. It wasn't uncommon at Lakes for someone to trip and just happen to land on the wrong end of a shiv. Accidents, like charity, begin at home.

Dooley had seen it all during his nine-year stay. All in all, Doome House still beat the hell out of doing hard time. The catch was the feel of isolation. Between the accidents and keeping up the March hare bit, Dooley made no friends. You couldn't rely on anyone else, and you couldn't let them rely on you. I took him to mean that making the wrong buddy just begged for an accident. That's right, Dooley said.

I asked Dooley how it was as far as putting on his mad act. Being crazy wasn't so hard, he told me. You just had to remember who you were dealing with. The staff doctors thought out every last thing. They analyzed how you walked, talked and blew your nose. They analyzed everything from how you parted your hair down to how you buttoned your shirt. They had a theory designed for everything, and everything designed to fit into a theory. So the idea's to never threaten them personally. Never make a stink in that sort of way. You make yourself as agreeable as possible, like you understand they're only here to help you, and you want their help, and you want to get better.

Dooley pointed out what you do is throw them off balance. You make them second-guess their theories, as least as far as your case is concerned. Dooley used all kinds of little bits. For instance, he explained, you could skip a meal. That's something they watch close. So when they ask why you're not eating you tell them a story about this inmate who said you were being poisoned. You make up some wild description, even come up with some dumb name for a bug that never existed. Or tell them you had to hide your shoes because the guards were trying to steal them. Stuff like that. The smaller the better.

Above all else, Dooley noted, one thing drove the shrinks to distraction like nothing else. Especially the head man, Dr. Frend. Anything inappropriate in the way of drooling, spitting, pissing or taking a crap sent them into the biggest uproar you've ever seen.

Like when Dooley first arrived and Friend interviewed him. Dooley made all cooperative like and everything was jake until he got up to leave. Frend realized Dooley had soiled himself and a very fine club chair. Frend went into a panic. He screamed for Dooley to hold it right there and sent for an army of guards to escort Dooley out of the office. For the following month the staff charted Dooley's each and every urination and defecation.

I thought it sounded unusual, that the head administrator for such a large facility would personally interview incoming patients. Dooley agreed that it was odd. Odd and commonplace for Dr. Frend, he said. I asked if the staff or inmates regarded Frend as some kind of psychiatric angel. Maybe he was the kind of guy who had to be as personally involved as possible with the patients. Dooley said "nuts" to that. Frend never treated anyone as far as Dooley knew. He never saw Frend anywhere outside of his office. Frend's interviews were cold, hard and prying. He didn't talk to you like the other doctors. He never tried to draw you out or ask how you felt about anything. Frend had only family members and crimes on his mind, cold facts, hard facts, and nothing else.

Dooley thanked me for a good talk, and said it was enough for now. I asked him if he was sure. He said he was very sure. He told me to return in five days.

The third time's the charm, all right. That's what I told myself when I sat with Dooley the following week. I flipped him a pack of Chesterfields. As he got a high sign from the guard, I struck a match. When the end of the cigarette reached the flame, I asked if he was ready to spill. He leaned back and the smoke curled out from his nostrils as the rubbery smiled wrapped itself from ear to ear. Donal Dooley nodded. This was his come on.

He asked if I knew about the heist that landed him at Lakes. About the $100,000 in gems. That the coppers had never recovered the ice. I told him I knew all about that. He said that was good.

He asked if I knew that he had a daughter. I told him I did. He explained that Kathleen, about to turn 21, was in a tight jam. Only money could get her out of the fix. She needed an awful lot of dough but quick. Dolan Dooley had something for Kathleen, and he had it in mind for me to get it for her.

Dooley wouldn't allow Kathleen to get it for herself. He didn't want her that directly involved. I asked him if anybody else knew about it. Like maybe Snoot, for instance. He asked aloud why Snoot would know anything. Why would he, I ventured.

I pointed out to Dooley that we both had one-way tickets in this thing. Maybe he was stuck, trusting me like he said. So I had to wonder why he trusted me.

It's all for his kid, Dooley said. He found himself out of time and out of choices. As simple as that. He told me he felt plenty confident about me. He'd take a chance on me, but, if I pulled something, anything, he'd find a way to square it, all right. Nobody on earth was ever going to screw with his little girl and get away with it. Naturally, he was all smiles as he said it.

I replied I found it fair enough, and he set out my instructions. He gave me an address for a house on North Kimball back in the city. Behind the house I'd see a smaller dwelling, like a coach house. Just beyond the coach house I'd locate a padlocked tool shed. What he wanted I'd find in the tool shed.

He repeated the Kimball address and gave me the combination to the lock on the shed. He instructed me not to wait. Do it right away, he said. Then follow up with Snoot. That surprised me, but he told me not to worry myself. Just take care of it right away and follow up with Snoot.

Dooley spun his way off the bench and rose. He said he didn't want to shake hands in front of the guards. He knew that I understood, he smiled. He ambled his way out of the hall and the screw tailed after him.

The whole set-up was loopy. I guess that fit into the picture. Sure. But there had to be more to it than what Dooley let on. The idea of his holding out didn't surprise me any. It didn't have me worried, either. Still, I thought I'd wait for daylight before taking on Dolan Dooley's treasure hunt. Dusk had settled in by the time I got back to the city. I felt tired, hungry, and just enough out of joint to call it a night.

I began the next morning with a boiling, hot shower, a full breakfast, and plenty of coffee. I found the Kimball address easy enough. I played it cautious and parked the coupe a block down.

A narrow, dirt driveway led passed the plain house, passed the coach house, and brought me to a green painted shed. This was a basic, rectangular number, about five feet in width and depth, with a flat roof about seven feet up. The paint job didn't show anything like nine years' worth of wear. The winter wind had a sharp bite to it and stung my hand as I dialed the stiff tumblers on the lock. The hook played stubborn, but finally worked loose. I removed the padlock, swung back the latch, and opened her up.

Snoot stared right back at me with a gaze as cold and lifeless as frozen marbles. His huge figure straddled a wheelbarrow, leaning against the back wall, his head wedged into the corner. His impeccable hair wasn't so impeccable. Stiff, little spikes stuck out on the crown of his head and at the temples. The temperature had transformed his handlebar into a frosted curlicue. Across his throat ran a fine slit, a razor-clean, evenly traced incision running the circuit of his fat neck. His shirt collar and topcoat could've used a drop cloth. Sure.

Brittle leaves littered the shed floor and partially covered a briefcase. It was one of those flimsy numbers, the type of case a smart lawyer like Snoot would use to tote loose papers. I found nothing in the case. I found nothing in Snoot's pockets. I found nothing else in the shed. Snoot told me nothing more.

I replaced the lock, wiped it down, and headed straight for the coupe. I had a long drive ahead of me. Before I hit the city outskirts I ducked into a diner to cop a black coffee. That's when I blew in a call to you boys. I figured it as good a time as any for the 18th district to meet Mr. Snoot. I hated to leave you to your own introductions, but I had a little matter to clear up. You could say a sense of Doome beckoned me. Sure.

That same, solitary bug in the Visitors Assembly droned away to himself. I awaited Dooley at another table across the big room. I'd just fired up a smoke when I heard the clang of iron doors and spotted Dooley hitching his way across the wide floor. The uniformed guard following him stationed himself at the closest wall.

Dooley dropped onto the bench, leaned back and swung his legs together, up, over and around to face me. Turning his head side to side, Dooley eyed me with that maddening grin plastered on his kisser. "Such a surprise to see you. I wasn't expecting no one."

"But you've probably got an idea why I'm here. Maybe you can you guess what brought me back to this godforsaken wasteland. It sure ain't for fun."

"Yeah, I guess I can pretty much guess, all right." He buried his tongue in his cheek and nodded his head. "I'm guessing you found something."

"I found something, all right."

"Up Kimball Avenue?"

"That's right."

"I thought you might."

"You mean you knew."

"No, I didn't know nothing for sure, but I had this inkling."

"You wanted me to find something, all right."

"I was sure you'd turn up something."

"That's an awful benign way to put it."

"You sure talk plenty fancy."

"And you talk in circles."

"A fella's gotta be careful what he gives away."

"I just don't see how you set up Snoot."

"Snoot?"

"You know what I found on Kimball."

"Oh yeah, I know. I know all about it. But it's not like you think."

"No?"

"No. That's right. Snoot set himself up."

"Exactly how is that?"

"I don't mind telling you, now. It's safe to, now."

"Try me."

"Snoot had no stake in this game. Not by a long shot. He dealt himself into this and made it his own headache."

"His headache's taken a permanent powder."

"That's right."

"Sliced up but good. None too pretty a job."

"That's right."

Even a brutal murder couldn't wipe the silly grin off Dooley's pan.

"See, like I told you, it shouldn't of had nothing to do with Snoot."

"Who, then?"

"Who? Dr. Viktor Frend, that's who."

"Uh huh."

"Oh, that's on the level. See, I been locked up nearly half my life. Juvie hall, county stir, state prisons. Now this joint. They're all of them the same in one way: each of them is its own private, little world. Each of them got their own, you know, class system. They're like tiny kingdoms, if you get me. There's always some ruler like Dr. Frend. And he's got his goon squad and underlings and a whole bunch of servants and it keeps going all the way down till you get to us bugs. So you got to learn the ropes 'cause each joint runs different, see? Like for instance, there's always an underground market, right? Some places the staff runs it. In other dumps the trustees run it. You with me?"

"I'm with you, sure. But it feels like we're taking the scenic route for no purpose. How's any of this tie up with Snoot or Frend?"

"I'm getting to it. But forget about Snoot, will you?"

"A lacerated throat's a little difficult to forget."

"Snoot stuck out his own neck."

"Some joke."

"Some victims are innocent, some ain't. Snoot brought this one on himself."

"I'll have to take your word on that one."

"I'm coming to it, I'm coming to it. You'll see."

Dooley held still for a moment, like he needed to double-check things before continuing. You could still hear the unintelligible drone of "Mumbles" at the far table.

"The guard?" Dooley asked. "He still holding up the wall behind me?"

"And yawning."

"Good. That's good. All's I'm trying to get across is that you have to get wise, see? You have to learn how each joint operates. Like this place stinks worse than most. Like when Frend called me in when I first arrived. I knew right off that was bad news, so's I played along. I played along and found out he didn't do that with every con. You know why?"

"It's your yarn. You tell it."

"Okay. You know what you've got here? What you got in any stir? You got a ready-made population of marks. We're captive victims, that's what we are. We got our nasty, little secrets and our family problems like anyone else. But they're all of them sitting there, just waiting, all at the disposal of anyone willing to go after them. And there's guys like me, cons who are supposed to have something they got away with waiting for them on the outside."

"Like a hundred grand in ice."

"Not just like that, exactly like that. That's what our friend Frend's after with his special sessions. It can take a few years, but you get to know the right guys from the wrong guys and you see what's happening. Frend's been milking the joint for one, long payoff. Whether he weedles it out of someone, extorts it, forces them to talk. And there's always plenty of informers."

"And that accounts for a lot of the accidents."

"Yeah, that's right. So I figure I have to do something about it."

"You're not trying to tell me you're some kind of crusader?"

"Naw, nothing like that. I gotta look out for myself. See, it doesn't matter whether I've got a cache or not. If people believe I've got it, that's like walking around with a target on my back."

"Uh huh."

"So it took awhile, but I finally set it up. It took awhile, but I got the proof I wanted and I set it up." For just a moment the silly smile turned inward.

"You're referring to the set up on Kimball?"

"That's right, but not the way you think. You plant a little misinformation, see, and things happen. You learn things."

"For instance."

"The right dough or favor buys plenty in any joint. I needed a set of eyes all the way from the top offices out to the garage. So's I paid up and I've been watching."

"Watching what, for instance?"

"Like what time of night or day people leave, and what time they come back. Like how much mileage they put on their car. What kind of debris you find on a bumper or in tire treads. You can learn a lot from what clothing a man launders and what he destroys. You can learn plenty from the kind of tool a man uses."

"Such as an exceptionally fine cutting blade. Like a scalpel, maybe?"

"Yeah, that's right. Like something, I don't know, a brain doc might use."

"And how did you figure that one?"

"That was the last piece. When we got the news just a couple hours ago."

"That had to be just after I discovered the body and phoned it in."

"Yeah, just like that. We got ourselves quite a pipeline, here. You know, the telephone system is truly a marvel of this modern age we live in."

"So you've built up your own case against Frend."

"That's right. I had to convince myself sure. You know, beyond a shadow of a doubt, like they say."

"Are you telling me you're going to try to send up Dr. Frend?"

"I didn't say anything like that. I'm not telling you no such thing."

"No?"

"I wonder about Snoot, the creep. I don't know if he double-crossed me on his own, or if he got involved with Frend."

"Maybe the cops will puzzle it out."

"Yeah, that's right. Maybe. But it don't matter. Leastways it don't matter to you, no more."

"How do you figure that?"

"You've done your bit, don't you see?"

"I guess I'm slow on the uptake."

"And you a private dick and all."

"What about Kathleen? What about all those jewels?"

"That little tramp? I ain't heard from her since my last stretch. I don’t even know if she's still alive and I couldn't care less."

"And I should I forget about the ice, too."

"That's right. Just like it never existed."

"Just like I should forget about collecting my fee."

"Now you see, you ain't such a bad sleuth after all. I mean, what would a convict who's lost his marbles possibly want with hiring a private detective? What kind of nut do you take me for?"

I gazed upon his sloppy, cheery face for a frozen moment. Then a piercing siren burst upon us like an unnerving, incessant shriek. Dooley swung off the bench in a flash as the guard ran up and threaded one of Dooley's arms.

Dooley glanced back at me as the screw tugged him away. "Sounds like another accident!" He couldn't have smiled any broader. The guard led Dooley out of the Visitors Assembly, forcing him to scuffle and hop in double time.

That left just me and Mumbles in the hall. I rose with the crushing weight of the siren in my ears. Mumbles' incessant babbling continued, but his eyes shifted quick. He took in the full perimeter of the abandoned room, then trained his stare on me. All of a sudden he shut his trap.

I returned his gaze and stepped slowly toward his table. He rose, ambled his way around the bench, and came towards me with short, shuffling steps, like some coolie in a B-picture. We met in the main aisle and stood face to face.

"What do you know?" I barked.

The taut skin of his face scrunched up and he wiggled his head sideways.

I repeated, louder, "What do you know?"

Mumbles smiled a smile almost as silly as Dooley's. We both leaned in as he began to speak with a cupped hand to his mouth.

"The good doctor!"

"Yes?"

"He's just left home!"

"Yes?"

"Permanent!"

Mumbles lowered his hands, but kept smiling. He turned away, then shot me a wink over his shoulder. He worked his way back to his bench with a hobbling and shuffling sort of walk, took his seat, and began murmuring again to no one.

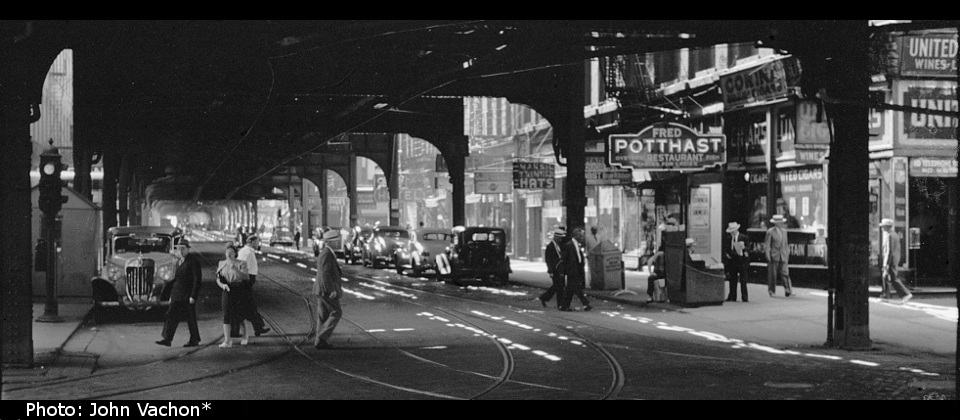

* The photograph displayed at the top of this page was taken by John Vachon as an employee of the Farm Security Administration, a federal government agency. For more information on the photograph, see http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1997006675/PP/.

|